“History is written by the victors — but truth is rewritten by the seekers.”

Who Drew the Map of the Buddha’s Life?

For centuries, the sacred geography of Buddhism has centered around India — Lumbini, Bodh Gaya, Sarnath, and Kushinagar. But this map was not handed down untouched from the time of the Buddha. It was largely shaped by 19th-century British colonial archaeologists who interpreted Buddhist texts with limited local knowledge, political agendas, and Eurocentric bias.

This article explores how colonial-era archaeology helped rewrite the spiritual geography of the Buddha’s life and why revisiting ancient Sri Lankan sources like the Mahavansa is essential to restoring what may be a lost truth.

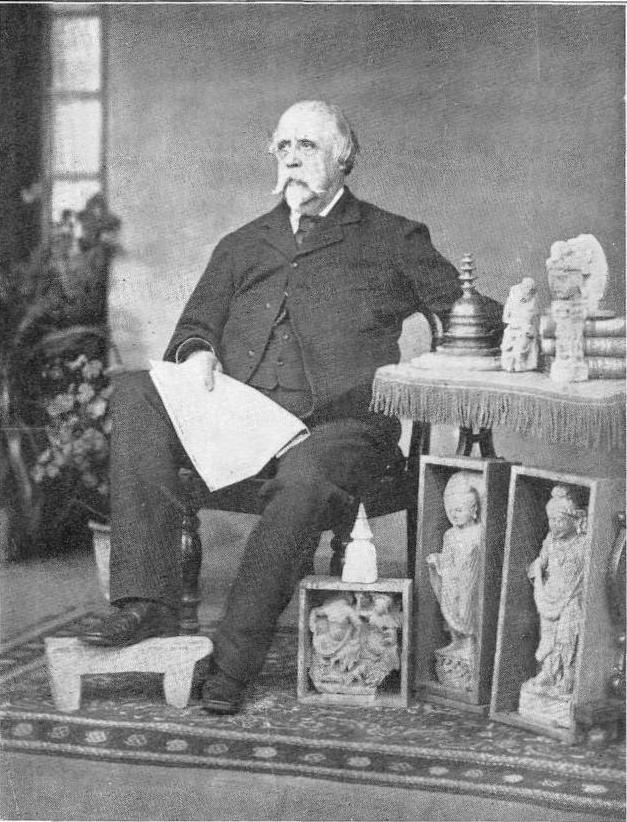

Alexander Cunningham and the Indian Re-mapping of Buddhism

Sir Alexander Cunningham, a British engineer and archaeologist, is often credited with rediscovering ancient Buddhist sites. He was the first Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India and played a key role in identifying Lumbini, Kapilavatthu, and Sravasti — often based on little more than vague textual alignments and proximity to pillars or ruins.

But here’s the problem:

- His translations of Faxian and Xuanzang relied on European editions, often mistranslated or misinterpreted.

- He ignored or dismissed Sri Lankan texts such as the Mahavansa and Saddharmaratnavaliya, which offer alternate geographies.

- He assumed all references in the Tripitaka referred to Indian locales, even when the described terrain did not match.

What the Mahavansa Was Telling All Along

The Mahavansa, written nearly 1,000 years before Cunningham’s work, provides a detailed account of the Buddha’s three visits to Lanka, including descriptions of places like Samantakuta (Sri Pada), Kelaniya, and his interactions with ancient tribes.

These descriptions:

- Match real Sri Lankan locations

- Reference distinctive topography (mountains, coastlines, rivers)

- Reflect a geographical center of the Dhamma in Lanka, not a foreign island

Yet these were dismissed as legend by colonial scholars who preferred to anchor Buddhism to the Indian heartland of their empire.

The Colonial Agenda: Why India Was Chosen

The colonial mindset aimed to:

- Centralize power and pilgrimage within British-controlled India

- Showcase Indian monuments like Sanchi and Gaya as imperial gems

- Reduce Sri Lanka to a peripheral island colony, not a spiritual origin point

By doing this, they not only elevated Indian Buddhism in global narratives but also erased Lanka’s foundational role in preserving the Tripitaka, hosting the first Dhamma councils, and safeguarding the relics.

Ignored Evidence: What Was Overlooked

Colonial archaeologists overlooked or underreported:

- Sri Lankan inscriptions predating many Indian relics (Inscriptions of Ceylon, Vol I–II)

- Pilgrimage accounts by Faxian that better align with Sri Lanka’s coastline and terrain

- Oral traditions and place names matching those in the Tripitaka but existing only in Lanka (e.g., Babaragala as Kapilavatthu)

Even when Lankan scholars brought these forward in the 20th century, they were often labeled as nationalistic reinterpretations, despite supporting textual and archaeological merit.

Conclusion: A Map Worth Redrawing

We do not deny that sacred Buddhist sites exist in India, nor do we dismiss their significance. But it’s possible that these locations reflect a later reinterpretation — perhaps rooted in Mahayana traditions such as the Five Dhyani Buddhas — rather than the historical journey of Siddhartha Gautama. Colonial-era mapping often overlooked Sri Lankan sources, misread ancient texts, and shaped a narrative that served the empire more than the truth. It is time we revisit the origin story with fresh eyes and ancient wisdom.

It’s time to take another look — not with bias, but with an open mind and an eye on the original sources.