For centuries, the sacred site of Lumbini in Nepal has been widely accepted as the birthplace of Prince Siddhartha Gautama, later revered as the Buddha. But what if history misread the signs? Deep in the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka lies Bambaragala Rajamaha Viharaya, a site that local tradition and ancient inscriptions claim was once the royal birthplace of a great sage. Could this be the true origin of the Buddha?

1. Geographic and Archaeological Setting

Bambaragala Rajamaha Viharaya is located in the Theldeniya region, nestled against a forested cliff face. The site is home to:

- Ancient cave dwellings

- Pre-Christian Brahmi inscriptions

- Natural stone platforms and pools

- A continuous tradition of Buddhist monastic use

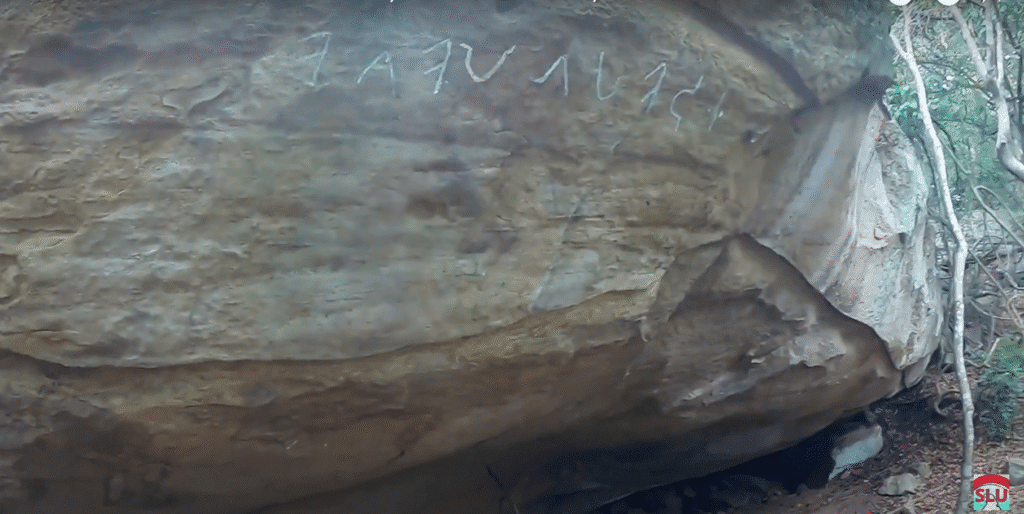

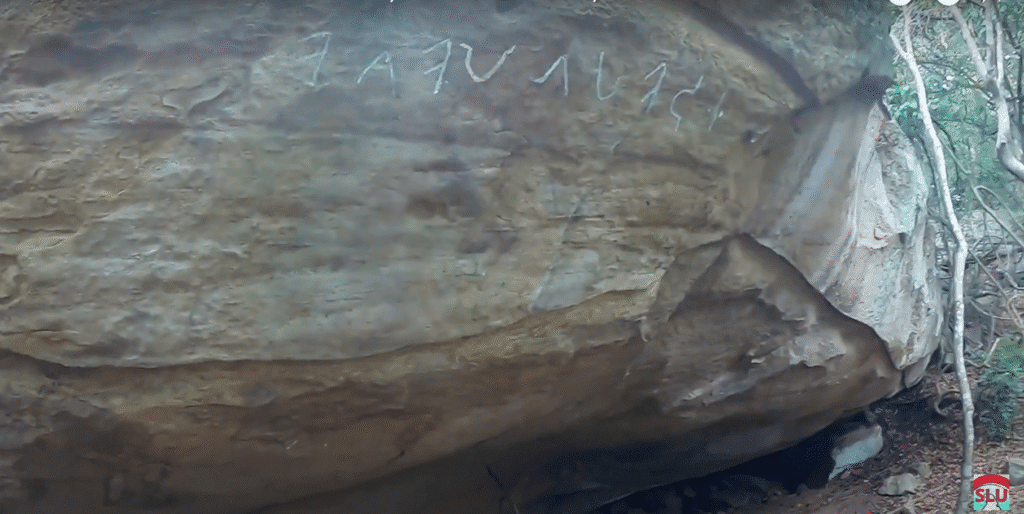

Archaeologists and epigraphists, including those in the Inscriptions of Ceylon (Vol. I), have noted the importance of the Brahmi cave inscriptions at this site, dating back to at least the 3rd century BCE—within centuries of the Buddha’s time.

2. Brahmi Inscriptions and Royal Lineage

Several inscriptions mention the donation of caves by royal family members, particularly princes and queens. One key inscription reads:

“Dameda puta…” – translated as “Son of the Damedian,” possibly referring to a noble clan in Heladiva (ancient Lanka).

The presence of royal references so close to the Buddha’s timeline has led many to propose that this was not just a monastery—but a royal residence.

3. Oral Traditions and Local Beliefs

Villagers around Theldeniya have long preserved the oral tradition that “Babaragala” (local name for Bambaragala) was:

- The ancestral home of a noble royal family

- The birthplace of a great sage or Bodhisattva

- A center for early Buddhist teachings

These stories predate colonial influences and were preserved by forest-dwelling monks and local temple lineages. Even today, women visit this site to pray for fertility—a custom believed to date back to Queen Māyā’s blessing under the sacred Sal tree.

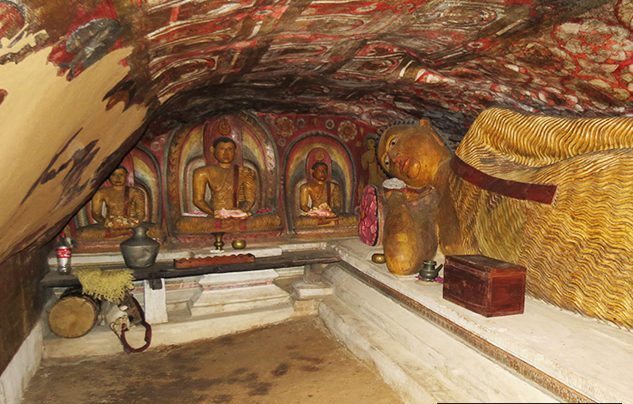

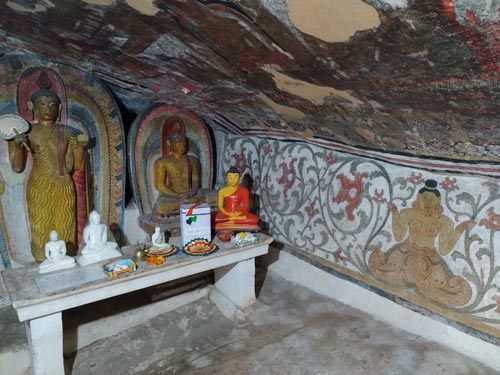

4. Iconographic Evidence in Temple Murals

Recent documentation of Bambaragala’s cave murals reveals astonishing evidence:

Sal Tree Imagery:

- Multiple murals depict Sal trees in full bloom.

- The blossoms align symbolically with the birth story of the Buddha under a Sal tree in Lumbini.

The Half-Dressed Female Figure:

- A mural shows a female figure holding tree branches, surrounded by blooming flora.

- This aligns with the image of Queen Māyā reaching to hold a Sal branch at the moment of giving birth.

- Unlike Indian depictions of Tharadevi (which are fully nude and erotic), the local figure is dignified and stylized—emphasizing sacred motherhood, not sensuality.

Repetition of a Distinct Female Form:

- Several murals across chamber show the same woman (hairstyle, earrings, position), reinforcing her identity as Queen Māyā.

These murals represent some of the most compelling artistic confirmations of a localized birth tradition.

5. Toponymy and Linguistic Echoes

- The name Theldeniya appears linguistically linked to “Thel Nadiya”, meaning a flowing stream or sacred river.

- Nearby, oral traditions link the area with Queen Mahāmāyā, and some older village names show resemblance (still under study).

- The ancient Mahaweli River was once called Ganga or even “River Ganges” in colonial and pre-colonial maps.

- Another river nearby, Hulu Ganga, is proposed to be the historical Rohini Nadiya, near which the Shakya-Koliya settlements were said to exist.

These hydronymic links mirror the Tripitaka descriptions of Buddha’s homeland.

6. Sacred Geography in the Chronicles

The Mahavamsa, Saddharmaratnavaliya, and Rajavaliya describe Kapilavastu not as a city in the Himalayan foothills, but as a hill-country kingdom within Heladiva (Sri Lanka). These texts describe the location as:

- Surrounded by forest and hills

- Accessible by rivers

- Guarded by natural rock defenses

This description aligns closely with Bambaragala—not the flat terrain of modern-day Lumbini.

7. Time and Travel: Sinhala Horas & Queen Māyā’s Journey

According to ancient tradition, one Sinhala hour (hora) equals 24 modern minutes, making a day 60 horas long. Queen Māyā’s procession took 11 Sinhala hours from her royal residence to the Lumbini grove.

In modern terms, this translates to 4 hours and 24 minutes. This time window fits travel from a royal palace in Teldeniya to the Sal tree grove at Bambaragala, affirming the logistical accuracy of this journey.

8. The 79 Caves of Bambaragala – A Forgotten Monastic Complex

One of the most astonishing aspects of Bambaragala Rajamaha Viharaya is its extensive cave network—nearly 79 caves have been identified across the site. These natural and partially carved shelters were historically used for meditation, dwelling, and teaching by monks, and many contain Brahmi inscriptions dating to the 3rd–1st centuries BCE.

“Vedu Lena” – The Cave of Birth

Among these, one cave stands out: locally known as “Vedu Lena”, or the Cave of Delivery. It houses ancient mural paintings that depict:

- A woman figure (possibly Queen Māyā Devī) under a tree

- Blossoming Sal trees with floral and symbolic motifs

- A semi-nude female figure holding plants—interpreted as a non-sexual, symbolic reference to birth and fertility

Local tradition strongly associates this cave with the birth of Prince Siddhartha, linking the murals and its name to the Lumbini birth narrative. Remarkably, even today, many women visit this site seeking blessings for childbirth, preserving an unbroken tradition of reverence.

Indrasala Guha – The Teaching Cave

Another cave has been identified by resident monks and local oral tradition as “Indrasala Guha”, mentioned in the Sakkapañha Sutta (DN 21) of the Digha Nikaya. According to the text:

“The Blessed One was dwelling at Indrasala cave on the slope of Mount Vediyaka, near the Brahmin village of Ambasanda…”

(Digha Nikaya 21 – Sakkapañha Sutta)

In this sutta, Sakka, the king of the gods, approaches the Buddha to ask deep philosophical questions. The cave identified at Bambaragala matches the topographical description: a rock shelter beneath a mountain ridge, overlooking a distant valley.

A Hidden Monastic Hub?

The density and distribution of the caves suggest a large-scale, active monastic community—possibly even a royal-supported forest monastery. This aligns with:

- The Brahmi inscriptions referencing royal donations

- The strategic location near rivers and trade paths

- The continued use by monks until modern times

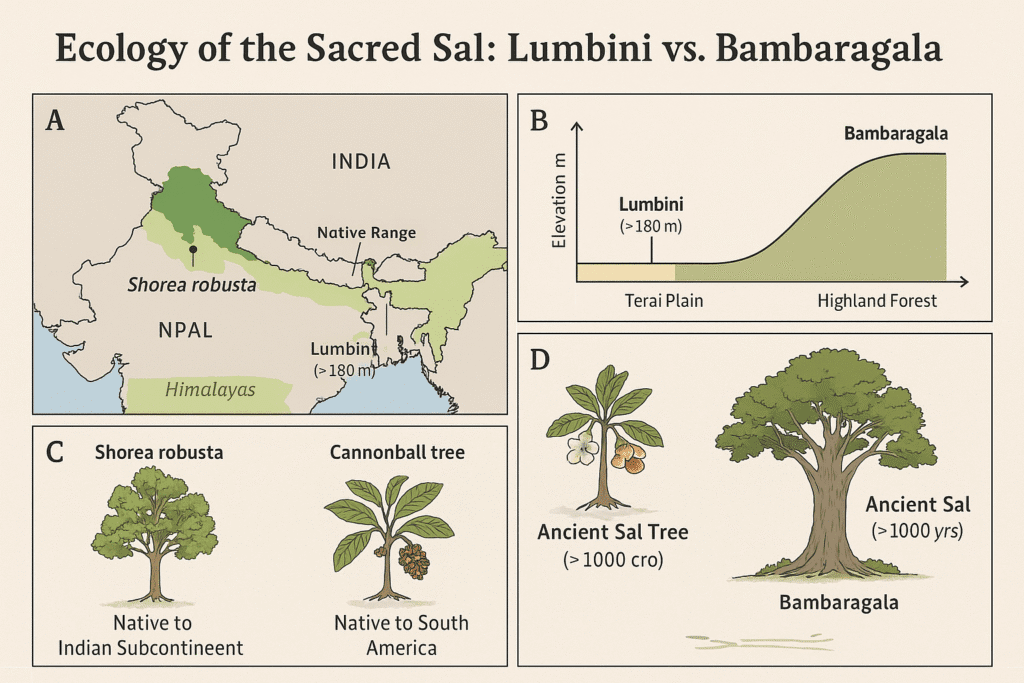

9. Ecology of the Sacred Sal Tree

Native Range of Shorea robusta (True Sal Tree):

- Sal trees are native to the foothills of the Himalayas, found mostly in India’s Terai region and lower hills, with only limited presence in Nepal’s Terai.

- Lumbini’s dry plains (~180 m elevation) do not naturally support dense Sal forests—any present Sal trees are likely planted or artificially maintained.

Bambaragala’s Unique Ecological Match:

- The site lies at ~600–700 m elevation in moist highland forest, suitable for true Sal growth.

- A 1,000+ year-old Sal tree still grows near Bambaragala temple—a living witness to the legend.

The Cannonball Confusion:

- Many Sri Lankan temples plant Couroupita guianensis (cannonball tree) mistaking it for Sal, though it’s a South American import.

- However, Bambaragala hosts the real Sal tree, not the substitute—a rare botanical truth supporting oral and visual traditions.

“Sal trees are not native to Lumbini’s environment—located on a dry Terai plain—while Bambaragala’s moist highlands support ancient Sal specimens. The presence of an original Sal tree at Bambaragala offers ecological credibility to local legends.”

10. Comparison with Nepal’s Lumbini

| Feature | Lumbini (Nepal) | Bambaragala (Sri Lanka) |

|---|---|---|

| Archaeological Age | Ashokan pillar – 3rd BCE | Brahmi cave inscriptions – 3rd BCE |

| Royal Connection | Inscription by Ashoka | Cave donations by royal family |

| Natural Environment | Flat plain | Forested, rocky hill sanctuary |

| Living Tradition | Pilgrimage site | Oral tradition of royal birth |

| Iconography | None linked to Sal birth | Sal tree murals, queen figure |

| Inscriptions | 1 Ashokan pillar | Multiple Brahmi inscriptions |

| Local Fertility Customs | Absent | Still practiced at temple today |

| Native Sal Trees | Marginal or planted | Ancient Sal grove present |

11. Why Was Bambaragala Forgotten?

Several factors contributed:

- Colonial-era scholars assumed all Pali references to “Lumbini” or “Kapilavatthu” referred to Indian sites.

- 19th-century nationalism in India emphasized a northern origin of Buddhism.

- Early archaeological efforts neglected the Sri Lankan highlands.

Yet modern Sri Lankan researchers like Prof. Raj Somadeva and monks like Balangoda Ananda Maithri Thero have begun reassessing geography and ancient toponyms.

12. A Call for Re-evaluation

If Bambaragala truly is the birthplace of the Buddha, then:

- The map of early Buddhism must be redrawn

- Pilgrimage routes should include Bambaragala

- Sri Lanka’s role in the Dhamma’s origin must be honored as foundational

“සකිය රාජකීය පවුලේ නිවෙස් බිමක් විය හැකිය.” – Tripitaka, Nalaka Sutta reference to Kapilavastu

References

- Inscriptions of Ceylon Vol I, Department of Archaeology, Sri Lanka

- Mahavamsa, translated by Wilhelm Geiger

- Saddharmaratnavaliya – Sinhala commentary edition

- Rajavaliya – historical chronicle

- Field interviews with resident monks of Bambaragala Viharaya

- Oral histories recorded in Theldeniya (2024), Buddha of Lanka Project

- Prof. Raj Somadeva – Archaeological Gazetteer of Sri Lanka

- Balangoda Ananda Maithri Thero – Siduhath Gouthama Buddha Charithaya

- Video documentation by Yathartha YouTube Channel

- Shorea robusta – Wikipedia

- Mongabay on cannonball tree misidentification

Conclusion

Bambaragala Rajamaha Viharaya is more than just a hidden temple on a cliffside—it could be the very cradle of Buddhism. As new light shines on old inscriptions, ancient murals, forgotten customs, preserved flora, and remembered rituals, we are left with one powerful question:

Are we ready to rewrite the map of enlightenment?

🛕 Future Research Areas:

- Linguistic analysis of ancient toponyms

- Dating the murals through pigment testing

- Correlating Sinhala hours with mapped distances

- Full archaeological excavation of the Bambaragala complex

- Comparative study of childbirth rituals in Lanka vs India/Nepal

- Botanical surveys of native Sal distribution in Sri Lanka

This article is part of the ongoing Buddha of Lanka research series.