“To read the Mahavansa is not merely to read history — it is to remember a map that was almost forgotten.”

Are Sri Lankan Texts Just Echoes of India?

A frequent objection to the Buddha of Lanka theory is the claim that ancient Sri Lankan texts — such as the Mahavansa and Saddharmaratnavaliya — are merely retellings of Indian sources. Some assume these works rely entirely on the Pali canon as preserved in India, or that they were written to support a “branch tradition.”

But this is a misunderstanding. These texts, particularly the Mahavansa and Saddharmaratnavaliya, preserve a unique geographical and cultural memory — one that diverges from Indian narratives, and in fact may preserve older, alternative identifications of key events in the Buddha’s life.

What is the Mahavansa?

The Mahavansa (literally “Great Chronicle”) was written in Pali by the monk Mahanama Thera of the Mahavihara tradition in 5th-century Anuradhapura. It is not a translation of Indian scriptures, but a chronological history of Lanka, beginning with the arrival of the Buddha.

“In the land of Lanka, to the peak of Samantakuta, and to Kelaniya, and to Nagadeepa — the Blessed One came thrice.”

— Mahavansa, Chapter 1

These visits are not metaphorical. The Mahavansa describes specific locations, tribes (Nagas, Yakkhas), and prophecies about Lanka as a future stronghold of the Dhamma. These statements are not found in early Indian texts and reflect local belief and memory.

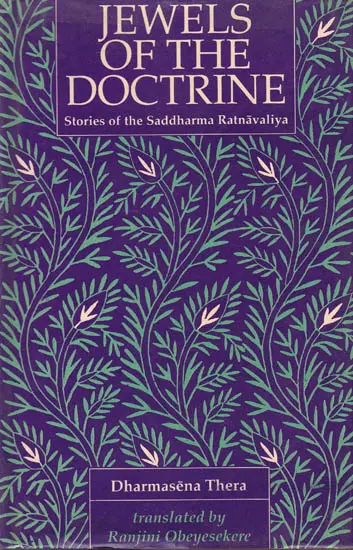

Saddharmaratnavaliya: A Forgotten Gem

The Saddharmaratnavaliya, written in 13th-century Sinhala prose, is a devotional and historical anthology based on older Buddhist teachings and folklore. Unlike the Mahavansa, it is not strictly chronological — but it includes vivid references to places, relics, and sacred mountains that match Sri Lankan geography.

For example:

- Mentions of Samantakuta (Sri Pada) as a pilgrimage site

- Retellings of Jataka stories located in Lankan landscapes

- Descriptions of the Buddha’s interaction with local tribes and spirits (interpreted as ancient clans)

These narratives are absent from Indian canonical scriptures but are deeply rooted in Sri Lankan identity.

Geographic Divergence: Hidden in Plain Sight

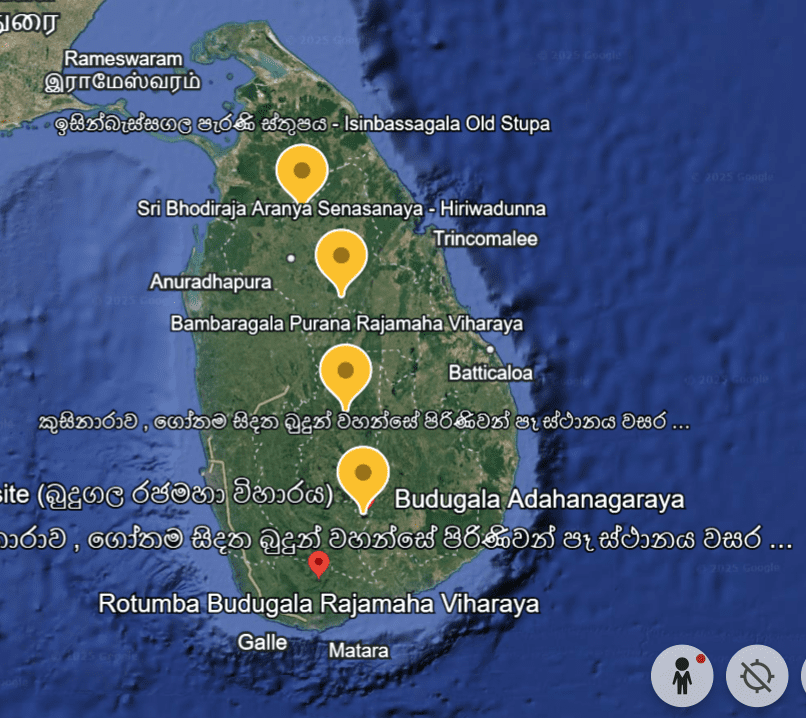

The places referenced in these texts often do not align with the geography of northern India:

| Event | Indian Identification | Lankan Alternative (in local texts) |

|---|---|---|

| Birth | Lumbini (Nepal) | Bambaragala (Theldeniya) |

| Enlightenment | Bodh Gaya | Hiriwadunna (Habarana) |

| First Sermon | Sarnath (Varanasi) | Isinbassagala (Anuradhapura) |

| Parinirvana | Kushinagar | Budhugala (Moneragala) |

These Lankan place-names are not forced parallels. They are:

- Referenced in ancient Brahmi inscriptions

- Connected to active places of worship

- Supported by oral history going back centuries

Do the Texts Derive from Indian Sources?

Partially — yes, in the sense that the Theravāda tradition shares roots with early Indian Buddhist oral transmissions. But to say the Sri Lankan texts are merely derived from India would be a serious oversimplification — and possibly a colonial-era misreading.

Here’s why:

- The Tripitaka was first written down in Sri Lanka, not India — during the 4th Buddhist Council at Aluvihare Rock Temple (Alu Lena), Matale (there is another theory for this too), in the 1st century BCE.

- While written in Pali, many traditions suggest that the Buddha actually spoke Maghadi, a language that Pali closely mirrors. Some scholars argue that Pali may be a standardized form of Maghadi, preserved in Lanka.

- The Tripitaka was written using Sinhala script, showing it was canonized and preserved locally, not imported from abroad.

- According to the chronicles, later Indian monks like Buddhaghosa translated original Sinhala commentaries into Pali and destroyed the originals, erasing earlier Lankan variations.

- A stone inscription in Mīnvila (Polonnaruwa District) reads “Magade”, a name dismissed as meaningless unless reversed. This could be a linguistic fossil of “Magadha” — carved in ancient Sri Lankan Brahmi, offering a material link to the term right here in Lanka.

- The Mahavansa and Saddharmaratnavaliya mention locations, rivers, and journeys that do not match Indian geography, but align with Sri Lankan landscapes.

- Events like the Buddha’s visits to Nagadeepa, Kelaniya, and Samantakuta are absent in Indian scriptures — but recorded clearly in Lankan tradition.

What Modern Scholars Say

- Prof. G.P. Malalasekara (founder of the Encyclopedia of Buddhism): “The Mahavansa must be read not only as a historical chronicle but as a reflection of the living tradition — memory embedded in place.”

- Dr. Senarath Paranavitana (former Archaeological Commissioner): “We should not dismiss Sri Lankan geographical identifications in Buddhist texts as metaphor — they may point to a suppressed historical map.”

Conclusion: Not Just a Chronicle, But a Compass

The Mahavansa and Saddharmaratnavaliya are not mere religious poetry — they are testimonies of a geography that was displaced. They remind us that the Buddha’s presence in Lanka was not spiritual metaphor, but cultural memory and sacred reality.

To dismiss them as “copies of Indian texts” is to ignore the voice of an island that has preserved the earliest form of the Dhamma and may hold the truest map of the Buddha’s life.

Thanks for your personal marvelous posting! I quite enjoyed reading it, you are a great author.I will make sure to bookmark your blog and will eventually come back sometime soon. I want to encourage that you continue your great work, have a nice morning!

very nice publish, i certainly love this website, carry on it